One of the people I follow on Twitter (I don’t recall who) called it “Baseball’s saddest day.” That’s probably an overstatement, but not by much. To put it bluntly, for baseball fans of my generation, Saturday sucked rocks.

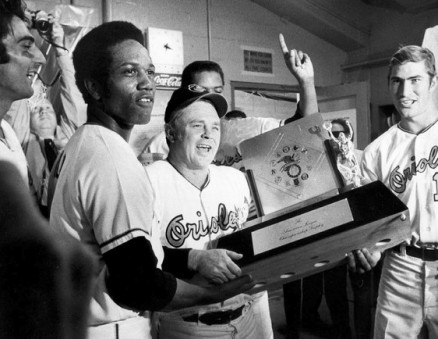

In one calendar day, we lost two giants of the game. First came the news that we lost the man I always felt was the greatest manager of his time, Earl Weaver. Incredibly, a few hours later, came word that Stan Musial had also passed. Weaver was 82 when he passed away of a heart attack during an Orioles’ “Fantasy Cruise,” and Musial passed away at his home at the age of 92.

I’ve read a few of the articles written in the past 24 hours about Musial and Weaver, but for my money, as always, the best came from Joe Posnanski. If you read nothing else about these two legends, read Posnanski’s articles by clicking here (for Musial) and here (for Weaver). As per usual, I’ll be stealing a bit from Poz in this article.

I’m not sure I could come up with two more different men to represent the game we love together as they approach St. Peter’s heavenly gates. Stan “the Man” will arrive playing “Take Me Out To The Ballgame” on his harmonica and be ushered straight through with a smile. Weaver, baseball’s self-described “sorest loser” will probably need to argue his way in. And that’s how it should be.

Musial is someone that Twins fans should be able to relate to. He’s the Cardinals’ version of our own Harmon Killebrew. I don’t think you could find a person who ever met either man who would have anything bad to say about him. He was a gentleman, a professional. You treated him with respect because of what he accomplished on the field and he treated you with respect because that’s just how he treated everyone.

How do Cardinal fans feel about him? They don’t just have a statue of Musial outside Busch Stadium in St. Louis… they have two of them.

They called him Stan “The Man” Musial. The nickname supposedly was given by a sportswriter after a game during one of Musial’s many amazing hitting streaks. The story goes that as Musial went to the plate, the fans started chanting, “here comes the Man.” Well, we all know how home town fans can do that kind of thing for their heroes, right? But here’s the thing… the Cardinals were playing in Brooklyn at the time.

But why shouldn’t he have been appreciated outside of St. Louis? After all, he treated fans on the road to 1,815 hits in his career… exactly the same number that he hit before his home fans in St. Louis.

His statistical accomplishments are simply amazing. They say he held so many batting records that they wouldn’t all fit on his Hall of Fame plaque. Seven batting titles. And, since batting average has fallen out of favor these days as a measurement of offensive productivity, he also led the National League in on-base percentage, slugging percentage and OPS at least six times each during his career.

And you could probably safely assume he would have done so one more year had he not missed the entire 1945 season while serving in the military during World War II. (Imagine, for a moment, if Joe Mauer had missed a season or two in his prime while doing tours of duty in Iraq or Afghanistan. There’s a reason they call it “the Greatest Generation.”)

I was not a National League fan as a kid, so I wasn’t as familiar with the NL stars as I was those in the Americal League. After all, I got to actually see Mickey Mantle, Al Kaline, Frank Howard and Brooks & Frank Robinson face off with Harmon Killebrew and Tony Oliva at the Met. I never saw Willie Mays or Hank Aaron play in person. Nor did I have the honor of seeing Musial play baseball in person.

But when you look at his numbers and you listen to people who did see him play… and those who were blessed to actually spend time with him… you know he was special. He was, after all, the Man.

I don’t think anyone would even pretend that Earl Weaver was as universally beloved as Stan Musial. Not anywhere outside of Baltimore, anyway.

But Musial’s greatness as a player was, to me, matched by Weaver’s greatness as a manager. It’s a cliché to say someone was, “ahead of his time,” but Weaver certainly was.

It’s disappointing to me that most of today’s fans probably just think of Earl Weaver as some kind of maniacal cartoon character of a manager, throwing tantrums and arguing with umpires. Then again, that’s an image Weaver certainly created for himself. But he was so much more than that.

He saw things in players that others didn’t. The best example is probably Cal Ripken. Ripken primarily played third base coming up through the minor leagues. He was, after all, 6’4” tall and infielders that size played at the corners. But Weaver moved the rookie to shortstop where he successfully stayed for a very, very long time.

He saw things in players that others didn’t. The best example is probably Cal Ripken. Ripken primarily played third base coming up through the minor leagues. He was, after all, 6’4” tall and infielders that size played at the corners. But Weaver moved the rookie to shortstop where he successfully stayed for a very, very long time.

As Posnanski points out brilliantly, Weaver could have managed for Billy Beane’s Oakland A’s (at least for a little while). Weaver loved walks and believed outs were precious and therefore hated bunts. He figured out what a player did best and then utilized him in ways that took advantage of those strengths. Just as importantly, he avoided using a player in situations he was unlikely to succeed in. He was among the first to embrace the use of a radar gun for pitchers, but he was less concerned about the MPH of their fastball than he was about making sure their change ups were at least 10 MPH slower.

He didn’t over-manage. He said more than once that he believed it was the manager’s job to argue with umpires because he was the person the team could most easily do without during a game. Once the line up was set, he left it to his players to play the game and decide the outcome.

And his teams won a LOT of baseball games. His Orioles teams finished first or second 13 times in the 15 years he managed the Orioles between 1968 and 1982 and went to the World Series four times in that stretch. (Weaver did return for a short time to manage the Orioles in the mid 1980s, but I, along with most Orioles fans I know, choose to conveniently disregard that time.)

In fact, I blame Weaver and his 1969 and 1970 Orioles for keeping what I consider the best Minnesota Twins teams in the franchise’s history from reaching the World Series. Killebrew, Oliva, Carew and the rest fell in the AL Championship Series both years to Weaver’s teams. In fact, Weaver’s Orioles swept the Twins both years.

Yet I always liked Weaver. I think it probably has a lot to do with seeing a lot of Weaver in my father (and vice versa), who was a high school baseball coach during the 1960s. Whenever I watched Weaver manage a game, my mind’s eye saw my dad.

I get that many others never held Weaver with that kind of affection. His own players generally didn’t care for him. He pushed them hard. He rubbed them the wrong way. He treated umpires… and others… with a total lack of respect, at times. I know all that. I don’t care.

He once told a reporter, “On my tombstone, just write, ‘the sorest loser who ever lived.’” I suppose it would be appropriate to honor that request. But I hope they find room on that tombstone for one more word. “Winner.”

Yes, Saturday was a sad day for baseball fans in St. Louis and Baltimore, but just as sad for baseball fans everywhere. Musial and Weaver, each in their own starkly different ways, epitomized the game of baseball as it should be played and managed.

We like to say the game should be played “the right way.” These two men demonstrated as well as anyone that there is no single “right way” to play the game of baseball… and that’s what makes it great.

Thank you Stan and Earl. We’ll never forget you.

– JC

” Once the line up was set, he left it to his players to play the game and decide the outcome.”

Where is the evidence for that? Weaver appears to have done the opposite. His teams had a whole bunch of role players around a handful of stars.

“He figured out what a player did best and then utilized him in ways that took advantage of those strengths. Just as importantly, he avoided using a player in situations he was unlikely to succeed in.”

This is what made him a great manager. He was an active manager who chose players for their particular skills and then putting them into specific game situations where they could use those skills to greatest advantage and be successful. He was noted for using statistics, but ones that current statheads would ridicule for “sample size”, like putting hitters into the game against a pitcher based on how well they done against that particular pitcher in the past.

“Weaver moved the rookie to shortstop”

Cal Ripken split time between shortstop and third base every year he was in the minor leagues. Weaver started him out at third base and moved him to shortstop in July after the guy he had there showed he couldn’t hit. But its not like Weaver came up with the idea of him playing shortstop.

“Weaver could have managed for Billy Beane’s Oakland A’s”

I doubt it. Beane inherited a great team when he started, but the teams he has built since have mostly been lousy. Last year was his first winner in 7 years. Weaver also valued defense a lot more than Beane appears to. Beane would have gone nuts when Weaver started making moves in games based on individual players skills that went against the “odds”.

My point about Weaver letting the players decide the outcome pertains to his disinterest in the bunt, hit & run, intentional walk and other micro-managing gimmicks. Yes, he loved to platoon. That was still more about line up management than micro-managing, imo.

Of course he didn’t use today’s modern statistics. But I do believe he would have used them to a greater degree than most of his modern-day counterparts if he were managing today. He used primitive stats and his memory because those were the best tools he believed he had to work with at the time.

As for Ripken, in his last two final years of minor league ball, he played 3B four times as many games as he did SS, so I’ll stand by my opinion that he “primarily played 3B” at that level and regardless of when, during his rookie year, Ripken was moved to SS by Weaver, the fact remains that it was Weaver who made the move.

As for whether Weaver could have managed for Beane, we’ll simply have to agree to disagree. As I wrote, they may have only been able to coexist for a while, because of the egos involved, but I do believe Weaver would have embraced much of what Beane believes in.

You’re welcome to disagree.

“Yes, he loved to platoon”

My point was that what made Weaver great was that he went well beyond “platooning”, which every manager does depending on their players. He paid close attention to individual pitcher-hitter matchups. He was adept at putting players in situations where they would succeed by paying close attention to all of their skills, strengths and weaknesses. Which is really the opposite of relying on “stats” to tell you probabilities.

I had no idea Weaver was responsible for moving Ripken to SS. Baseball, the owners, or the Hall of Fame maybe, owes him a small token gesture of gratitude for that alone. What a baseball mind, a general, and entertainer.

I never had the pleasure to watch Musial play. I wish I had. It always amazes me to look up the careers of guys who put up Hall of Fame stats, and yet left in their primes to join the service. What a life. The man may not have brough in the mega contracts we got today, but he lived through so much of this country’s “prime.” That’s something you can’t really mourn. I can’t anyway. It must be celebrated. So a toast of my Coke Zero to Stan the Man, and making the most of the prime years in life!

Jim,

This was well written my friend!